The right to decide

- Eurozine Review

1/2018

‘Soundings’ and ‘Syn og Segn’ debate sovereignty and citizenship; ‘Index on Censorship’ asks if we protest enough – or too much; ‘Osteuropa’ makes a sober assessment of Czech politics; ‘Revolver Revue’ talks to concept artist Karel Miller; ‘New Eastern Europe’ investigates a growing generation gap; and ‘L’Homme’ revisits sisterhood.

Soundings (UK) 67 (2017)

Hostility to Catalan regional autonomy from Spain’s conservative People’s Party since 2010 is what has catalysed the current secession debate, argues Nora Räthzel in Soundings. In an informative article, she explains the positions on independence of Catalonia’s political parties, looking especially at the role of the social democratic PSOE – whose opposition to a referendum was, among other things, the stumbling block to a coalition with Podemos in 2015, and whose refusal to negotiate with the Catalan government during the current crisis is partly responsible for the stalemate.

The right to decide is supported by between 70 and 80 per cent of the Catalan population, while only around half support independence as such, writes Räthzel. And yet parties that defend the democratic process – which include Podemos and its Catalan branch Catalunya en Comú – are now squeezed between hard-line independentistas and far-right defenders of the unity of the Spanish nation. ‘The European left should be supporting Podemos and other left groups demanding the right to decide,’ argues Räthzel. ‘This would not imply support for independence or any kind of nationalism – whether or not in progressive form.’

Noncitizenship: ‘The intrinsic value of citizenship is rarely questioned within liberal democratic discourses,’ writes Tendayi Bloom. ‘Even critics often focus on whether equality of citizenship is being realised … They seldom question the underlying assumption – and promotion – of liberal citizenship as the only legitimate relationship with a state.’ Looking at the negotiation of liberal citizenship by the North American Iroquois, Aboriginal Australians and the Haitian revolutionaries of the eighteenth century, Bloom argues that a way needs to be found, ‘within liberalism, to understand forms of politics that are more than “citizen” politics’.

Disrupted childhood: Perceptions of the poor prospects of children in care are reinforced in children’s literature and comics, writes Kirsty Capes. There, ‘they do particular harm because they teach children from disadvantaged backgrounds that they are destined to fulfil their inherited predisposition’. One exception are the children’s novels of Jacqueline Wilson, in which ‘disrupted childhood is portrayed as symptomatic of larger social problems such as working-class poverty, mental illness, and domestic violence’. ‘Intersectional analysis’, writes Capes, ‘would benefit from the inclusion within its terms of reference of those who start out in life with major obstacles to “success” in the form of family difficulties.’

More articles from Soundings in Eurozine; Soundings’ website

Syn og Segn (Norway) 4/2017

A dossier in Syn og Segn on the Sami nation, with its ancient culture and growing political self-awareness, is fascinating both for its insights and its contradictions. ‘Belonging’ is a difficult issue, mainly as definitions of true Sami-dom vary, as do languages and national affiliations. Although the total population numbers only up to 100,000, the Sápmi – the Sami territory – covers a huge space stretching through Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.

Sami are, in the main, modern Europeans. In interview, writer Sigbjørn Skåden insists that, nowadays, it’s fine to be a Sami on your own terms, even for those who used to be outsiders: ‘hip-hop Sami and homosexual Sami and those who can’t speak any Sami language’. Nonetheless, it is still part of the national narrative that Sami roots go deep into an ancient culture of nomadic reindeer herders, hunters and craftspeople.

Five writers deal with the state of the Sami nation today. Topics include the Sami parliament and its electorate, the influence of local councils, environmental issues, the iconography expressed in clothing and old customs, and the reconfiguring of an orally transmitted culture into modern media. The concept of ‘decolonization’ crops up everywhere: native peoples freeing themselves from agencies that separate them from the traditions they were born into.

Identity and citizenship: An interview with the musician Mona Ibrahim Ahmed illustrates how embracing a new culture can profoundly change your sense of identity. Ahmed, who grew up in Norway, speaks of how, in her late teens, she decided to follow her instincts and distance herself from her Somali origins. Despite pressure from her family, she abandoned its Muslim traditions for the mainstream culture, which gave her freedom to speak, act and dress as it suited her. But her application for Norwegian citizenship was rejected after four years of inexplicable official headshaking over her inability to define her exact origins in nomadic Somali clans: ‘I feel I have no human rights any more’.

More articles from Syn og Segn in Eurozine; Syn og Segn’s website

Index on Censorship (UK) 4/2017

In Index on Censorship, Micah White, one of the co-founders of Occupy Wall Street, asks ‘is protest pointless?’ Pointing to Occupy, Black Lives Matter and the Women’s March, he remarks, ‘I supported all of these causes, yet I saw that their tactics were failing … And now activism is at risk of irrelevance.’ He blames a pincer attack by ‘an insular activist clique that promotes a false triumphalist narrative, eschews collective criticism and ostracizes all who challenge movement dogma’ and ‘the mass culture industry, social media monopolies and the “influencers” that profit from transforming revolutionary activism into commodified social marketing.’

1968: Fifty years after the Prague Spring, journalist Robert McCrum recalls Milan Kundera’s land of ‘laughter and forgetting’. Now, the city of Kafka and Masaryk, once ‘the provincial capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, steeped in German language and culture – has become anglicized and modernized.’ McCrum remembers smuggling bananas into the country in the 1960s: ‘Today, there are bananas in abundance … What’s missing is the excitement that once came with a first reading of Kundera’. Such writers are no longer banned, but ‘sadly, they seem to be only half-remembered – and virtually unknown to a new generation of twenty-first-century Czechs. That’s not a joke.’

Book fairs and the far-right: A series of interviews and articles respond to the furore over far-right publishers’ involvement in book fairs. Award-winning author Peter Englund chose to stay away from last year’s Gothenburg Book Fair ‘because it meant that I would have to appear on the same stage – broadly speaking – as these rightwing extremists … and that would have helped to normalize their views.’ He advocates resistance: to avoid the fate of the Weimar Republic, ‘democracy in Europe … has to be belligerent’. Fellow author Ola Larsmo, on the other hand, decided to attend ‘along with other writers who stated that they would not be run out of the place by extremists’. Tobias Voss, director of the Frankfurt Book Fair’s international section, writes that banning titles or people is only justified by the law: ‘A functioning democracy must tolerate dissent … The fair does not see it as its duty to establish its own political, moral or aesthetic criteria for permitting or forbidding things.’

More articles from Index on Censorship in Eurozine; Index on Censorship’s website

Osteuropa (Germany) 9–10/2017

Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš has been seen as the latest in the series of illiberal democrats in the region, however comparisons with Orbán or Kaczyński are false, writes Osteuropa editor Volker Weichsel. True, Babiš’s name does not stand for rule of law, transparency and consensus. And he indeed represents a concentration of economic, media and political power. However, unlike his Hungarian and Polish counterparts, Babiš will not oversee an authoritarian restructuring of the political system. First, because the Czech electorate has not given him a sufficient mandate; and second, because Babiš himself has no social-political programme anything like as clear as Fidesz or PiS. Pragmatism and efficiency are his watchwords, not the defence of supposedly national values.

Eurosceptic notes struck by Babiš during his election campaign are, if anything, proof that he is ‘willing to play with fire in order to maximize votes’. His government, writes Weichsel, is unlikely to depart from existing Czech EU policy: ‘as little integration as possible and as much as necessary in order to prevent the formation of a core Europe that excludes the Czech Republic’. How Czech politics develops will depend a lot on the outcome of the second round of the presidential elections. Instead of exerting a conciliatory influence, the incumbent Miloš Zeman has acted as an independent political actor and has so far protected Babiš. If Zeman is re-elected, which looks likely, Czech politics will deteriorate further, Weichsel predicts.

Journalism: Martin Pollack, the acclaimed Austrian author, journalist and translator, talks in interview about his National Socialist family history and its relation to his writing on Polish and Central Eastern European history. According to Pollack, his characteristic combination of autobiography, journalism and historical essay owes much to the Polish tradition: ‘The Poles are great readers of reportage. Readers need to be cultivated for that. Here, when you approach a newspaper with a text of over ten pages of manuscript, editors shake their heads: who on earth will read that? There are fewer and fewer places where you can publish longer texts. In Poland, it’s still possible, thank heavens.’

More articles from Osteuropa in Eurozine; Osteuropa’s website

Revolver Revue (Czech Republic) 109 (2017)

As part of a series on Czech conceptual art in the 1970s, Revolver Revue features an in-depth interview with art historian, visual poet and body artist Karel Miller, illustrated by photos of his work. Born in Prague in 1940, Miller worked for the Czech National Gallery; after being demoted to a clerical job during the ‘normalization’ era, he began to study and translate texts on Zen Buddhism and to experiment with conceptual art.

‘I was captivated by the directness of Zen Buddhism, the fact that it can manage without the mediation of words. It was a spiritual world not ruled by logical concepts or logical thought. European philosophers can’t manage without logic, but here I suddenly encountered a world that bypassed it, and this helped me realize that I can express myself using my own body […] And since everything in the world of art is immediately labelled and pigeonholed, this became known as body art, which had several ‘varieties’, but I just filed it all under conceptual art.’

Though Miller and his conceptualist friends were not allowed to travel, their events were photographically documented at dozens of exhibitions worldwide. The artists evaded the censors by posting the pictures in unsealed envelopes marked PRINTED MATTER, until an official at the Czech consulate in Milan spotted their names in a newspaper review and alerted the authorities back home.

Electronic art: Petr Babák introduces a recent art installation that may be regarded as a kind of body art for our technological era. In Dr Brain’s Consulting Room by Jonáš Strouhal, members of the public could generate abstract paintings by means of their own thought processes:

‘Through a pair of 3D glasses, you get a glimpse of a space Jonáš has created for you. Dr Brain connects you to his machine by a tangle of ropes he slaps into your hair with some gel. High mountains appear on the display and your brain heats up instantly, turning you into a real Banksy or, if you get carried away discussing cybernetics with Dr Brain, into a pointillist painting, or even a fastidious Flemish still-life.’

More articles from Revolver Revue in Eurozine; Revolver Revue’s website

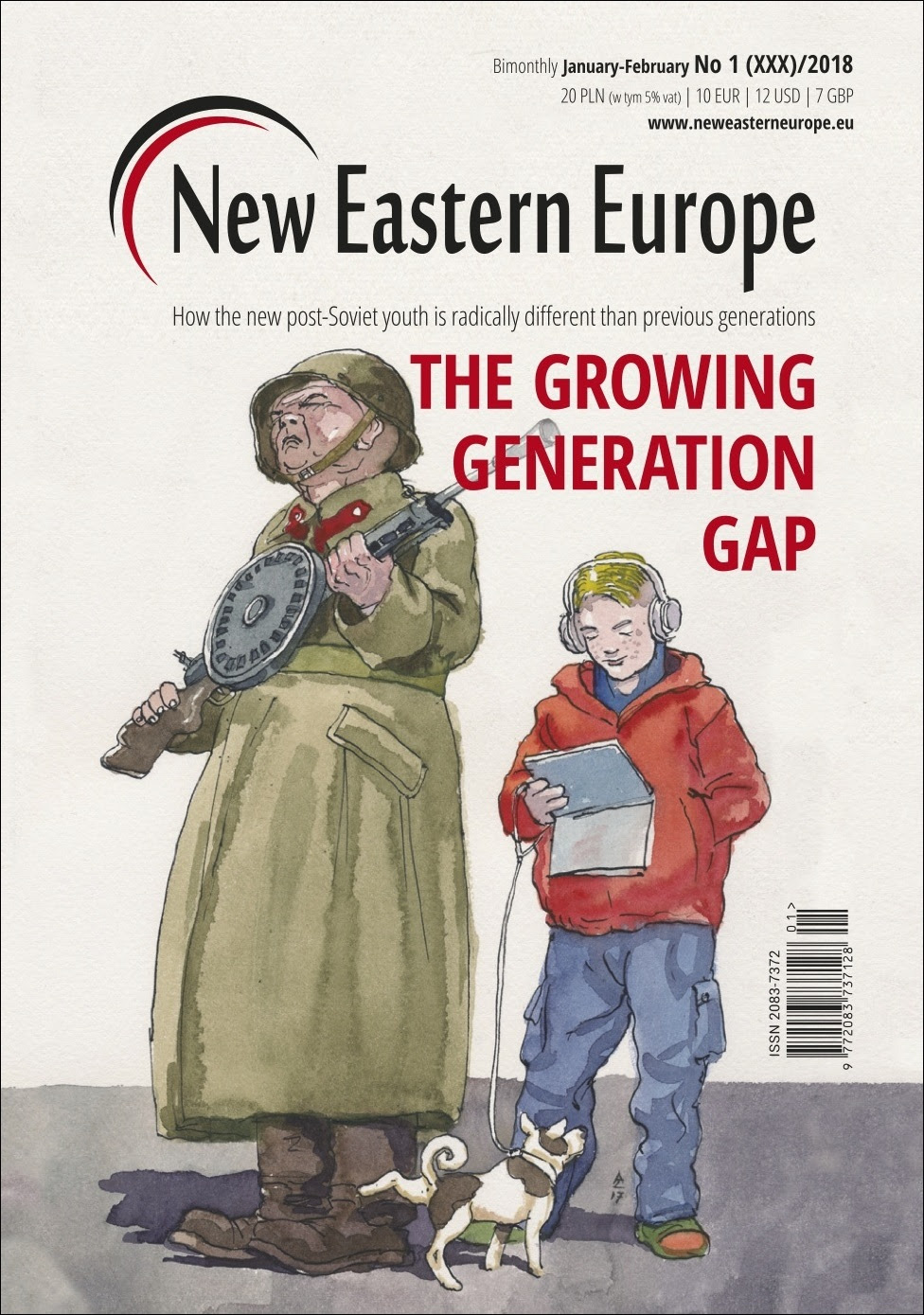

New Eastern Europe (Poland) 1/2018

In New Eastern Europe, Dagmara Moskwa discusses revisionism in the teaching of history in Russian schools and specifically the introduction of new textbooks which present an officially accepted version of history. Olga Vasilyeva, who was nominated education minister in August 2017, ‘is known to have with close ties to the Orthodox Church’ and has published articles and given lectures that ‘illustrate her open approval of the Stalin era’.

Recent textbook reforms have produced some Kafkaesque results. Moskwa cites the example of a teacher in Perm who was prosecuted on charges of ‘rehabilitation of Nazism’ for writing online about the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland – an event which official Russian history books openly discussed in the 1990s, but now gloss over.

Belarus: In neighbouring Belarus, the state’s approach to history is more nuanced – or confused, depending on your point of view. ‘Even though a quarter century has passed since regaining independence, Belarus has still not created its own, common historical policy, nor has it built a widely accepted national identity,’ writes Maxim Rust, who examines how conflicting currents have tugged memory politics back and forth.

Most recently, Russia’s actions in Crimea and Ukraine have forced President Aleksandr Lukashenka to change tack: ‘The regime realized that playing the Russian card could be risky for the country’s independence in the long term. Hence, the narrative changed again. It was replaced by a discourse that makes references to the Soviet past, but also shows Belarus’s special role in it.’

Ukraine: Marek Wojnar tells the mostly forgotten tale of ‘Green Ukraine’: the dream of Ukrainian settlers who began colonizing the Russian far east first in the seventeenth century, and in earnest ‘as a result of the opening of a direct sea route between Odessa and Vladivostok in 1883’. Their fate got tied up with Ukrainian nationalism post-1917, and an alliance with imperial Japan was mooted, but scotched by language issues. Now, outside fringe nationalist circles, ‘the memory of Far Eastern Ukraine and related colonial fantasies are fading away.’

More articles from New Eastern Europe in Eurozine; New Eastern Europe’s website

L’Homme (Austria) 2/2017

The concept of ‘sisterhood’ dropped out of feminist discourse after black and post-colonial feminists criticized it as Eurocentric – bel hooks’s Ain’t I a Woman? (1981) was a landmark in this shift between first and second-wave feminism. In L’Homme, Luisa Passerini – Italian pioneer of oral history (Fascism in Popular Memory: The Cultural Experience of the Turin Working Class, 1984) – explains to editor Almut Höfert how she and other radical feminists were critical of the discourse from the start:

‘We were absolutely against the concept because it metaphorically implied family groups and biological relationships. “Sisterhood” was also connected to mothers and daughters, and to the idea that women were predetermined to be mothers. Instead, we believed in relationships built not on the family but on choice. This was part of our striving to become complete subjects – above all in our relationships with one another. In radical feminism, it was not so much about equality between men and women, but primarily about relationships between women, which could be solidary but could also be conflictual. In order to be a complete subject, conflicts must also be contested in a civilized way. Equality with men was secondary, we were interested in solidarity among ourselves but in the right to contradict one another and develop.’

Sister figures: Criticism of a promise of sisterly equality that ignores differences and relations of power is the starting point for the issue as a whole. Contributions seek to understand the history of sisterhood in terms of different interests, rights, meanings and impacts. ‘There is not just one sister,’ write the editors, ‘but various sisters, or “sister figures”, who through their respective relationships obtained historical and cultural outlines.’ The focus includes Michaela Hohkamp on the role of sisters in early-modern noble society; Stefani Engelstein on sibling relationships, gender differentiation and financial allegiance in the capitalist nineteenth century; and Sebastian Kühn on the gender politics of the kitchen in the courtly households of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Germany.

More articles from L’Homme in Eurozine; L’Homme`s website

The Eurozine Review presents a selection of the latest issues of Eurozine partner journals, summarizing their contents in English as a way of encouraging cultural and political dialogue between national public spheres in Europe.

Published 17 January 2018

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.