A continent divided by experience

- Eurozine Review

10/2019

‘Ord&Bild’ thinks long-term about Europe; ‘New Humanist’ laments New Atheism’s irrationalist legacy; ‘Mittelweg 36’ explores new directions in the sociology of violence; ‘L’Homme’ reads historical case studies of ecstatics and intersexuals; and ‘Revista Crítica’ looks back at Afro-Yugoslav film and post-colonial solidarities.

Ord&Bild (Sweden) 2/2019

Ord&Bild provides an alternative to much post-EP election debate with some long-term thinking about what has shaped, and is shaping, the ideological climate in Europe. Historian Håkan Forsell talks of a continent ‘divided by experience’, arguing that the aestheticized western European vision of the East as the ‘true Europe’ is the root of the persistence of an ‘us and them’ divide.

Reportage: In an image/word collaboration, artist Axel Karlsson Rixon and historian Mikela Lundahl Hero report on the refugee experience – or rather, what goes through the mind of a worker in a refugee camp. In photographs and short, reflective prose, the two authors, who volunteered in a camp in Skaramagas, close to Athens, tell a story of rage and dejection: ‘Impossible to go back. Impossible not to go back. Impossible to abandon all these people. And still completely impossible to make a real difference.’

Film: Could the city that inspired the play on which the film Casablanca was based in fact have been Tangiers? In Swedish-Finnish-Indian writer Zac O’Yeah’s tall tale about a hunt for the real ‘Rick’s Café’, the refugee experience reappears. Not all that long ago, boats on the Mediterranean carried people in the opposite direction than they do today, away from war-torn Europe to the refugee camps of North Africa.

Fascism: Karolina Enquist Källgren traces memories of the Franco era in Spanish institutions today. After the dictatorship, new structures were created that preserved semi-official ultra-nationalism. Spain’s painful dilemma about how to handle the remains of Franco himself, as well as those of the many victims of the civil war still resting unidentified in mass graves, is so hard to resolve for precisely this reason.

Also: Lars Hermansson on living on the slopes of Vesuvius, awaiting catastrophe (as a mode of the times); and Emi-Simone Zawall on her journey to Drohobycz, the home of Polish modernist Bruno Schulz, once located in Poland, now in Ukraine.

More articles from Ord&Bild in Eurozine; Ord&Bild’s website

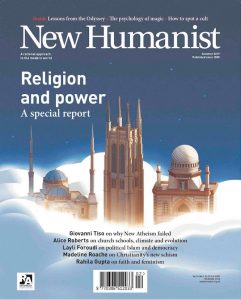

New Humanist (UK) 2/2019

In New Humanist, Giovanni Tiso reads the recently published transcript of the famous 2007 conversation between Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and Sam Harris. The so-called ‘New Atheists’ promised to reclaim ‘science’ and ‘reason’ from religious ‘irrationalism’. Instead, they revived an eighteenth-century scientism in order to heavy-handedly destroy a strawman of their own making. ‘How’, Tiso asks, ‘did such a transparently flawed intellectual project hold sway for so long among so many?’

9/11 is certainly part of the answer. But there was another reason: social media. ‘If, like the New Atheists, you believe that the most complex questions can be abstracted from their social context and reduced to binary opposites, then Twitter is the perfect vehicle for your ideas’. By ridiculing their targets and treating Islamic extremism as if it were ordinary religious practice, the New Atheists ironically influenced figures of the new irrationalism: a whole generation of online conspiracy theorists who cloak their prejudices in the respectable garb of scepticism.

Tunisia: The Islamist Ennahdha party in Tunisia balances religious commitments with exactly the kind of secular modern governance that the New Atheists claimed was impossible for Muslims, writes Layli Foroudi. Repressed by successive post-independence governments, Ennahdha joined an Islamist-secular coalition following the Arab Spring. The coalition was praised for its progressiveness as its new constitution enshrined sexual equality, omitted Sharia law, and maintained the separation between ‘mosque and state’. Leftists, however, fear that these are ‘fig leaf’ measures and worry what would happen if Ennhadha governed alone. Some former Islamist voters, meanwhile, complain that the party cares more about governing than defending Islam and the revolution.

Ukraine: Madeline Roache identifies similar complexities in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s split from the Moscow Patriarchate. Belonging to the breakaway ‘Kyiv church’ is, for some, a way of showing that they embrace liberal values and oppose Russia. Others, often rural believers, find that threatening, even if they already feel betrayed by Moscow.

More articles from New Humanist in Eurozine; New Humanist’s website

Mittelweg 36 (Germany) 1–2/2019

Mittelweg 36 devotes a special issue to the sociology of violence – over the past two-and-a-half decades the defining interest of its publisher, the Hamburg Institute for Social Research. The back-catalogue of the Institute’s imprint – Hamburger Edition – offers a useful survey of the recent sociology of violence in Germany and internationally, writes HIS director Wolfgang Knöbl.

Key texts: Two works, both published in 2008, stand out. Vertrauen und Gewalt (‘Trust and violence’) – by the literary scholar and HIS founder Jan-Philipp Reemtsma, discussed how modernity ‘could continue to reproduce the postulate of abstinence from violence, despite regular disappointment’. Though the book’s brilliance was widely acknowledged, write the editors, it failed to gain traction in sociology. The opposite has been true for Randall Collins’s Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory, an ‘instant classic’ translated into German in 2011. Collins’s underlying question was how antagonists in violent situations are able to overcome the emotional barriers that normally prevent individuals acting violently: fear, tension, passivity.

Both works – and the sociology of violence in general – prefer a ‘situational’ and ‘precise description of violence’ (Knöbl) over analysis of structural or emotional factors. The issue seeks to find ways beyond this ‘micro-sociological’ and ‘situational’ paradigm.

Terrorism: Reconstructing the Charlie Hebdo attacks in 2015, Thomas Hoebel examines how ‘absent’ third parties influence the dynamic of violent events. Particularly the killers’ show-down with the French police suggests that they were acting for the benefit of an ‘imaginary public’, for whom they wished to appear as ‘fearless jihadists seeking their own martyrdom’. In similar vein, Vincenz Leuschner analyses the communicative dimension of school shootings and other forms of planned violence – including hate crimes, political violence and mafia violence.

Riots: Stefan Malthaner, meanwhile, challenges the assumption that violent rioting is the result of collective irrationality. On the contrary, accounts of participants in the Hamburg riots of 2017 suggest rioters behave in a calculated and ‘socially competent’ manner.

Also: Wolfgang Kraushaar on the rise of Greta Thunberg as icon of climate protest and her refusal either to be impressed by the flattery of the powerful or to be intimidated by the criticism of reactionaries.

More articles from Mittelweg 36 in Eurozine; Mittelweg’s website

L’Homme (Austria) 1/2019

L’Homme – The European Journal for Feminist Historiography – looks at how medicine, psychiatry, literature and fine art interacted in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries to produce the ‘case study’. Originating in the early Renaissance, the case study as a form of scientific writing is closely related to literary narratives of ‘case’, write issue editors Regina Schulte and Xenia von Tippelskirch. Criminology and psychiatry in particular influenced literary descriptions of ‘type’: the social outsider, the exotic foreigner, the master thief or the female poisoner. With a revival of the case study in recent historiography and sociology, the question arises as to what constitutes a ‘case’, and to the dialectic of particular and general – a paradigmatic concern for gender studies.

Psychoanalysis: Historian of medicine Esther Fischer-Homberger✝︎ looks at the case of the religious ecstatic Madeleine, observed and treated by the French psychologist and psychotherapist Pierre Janet between 1896 and 1904. Madeleine reflected not only the medical image of her own illness, argues Fischer-Homberger, but also the relationship between therapist and patient. Janet, for his part, refused to frame Madeleine’s visions either as revelations (as the Church insisted) or as pathological hallucinations (as demanded by secular science). Instead, he based his case history on his patient’s self-observations and self-portraits. What emerges is a case history ‘cut from a rich fabric fashioned from interwoven strands of history and individual relational narratives’.

Intersexuality: In 1801, Maria Dorothea Derrier was admitted to the Charité hospital in Berlin suffering from scabies and came out having been diagnosed as a ‘female hermaphrodite’. Before x-ray technology, intersexuality was a matter of intense scientific speculation, something which Derrier, or Karl Dürrge as he called himself, took advantage of, earning a living as a touring medical specimen. As Stephanie Sera writes, medical doctors’ fear of being ‘duped’, both by the body and by the person, derived from their concerns about their professional reputation. In cases like Dürrge’s, this led to ever greater emphasis on the exactitude of observation. It was only with the emergence of psychoanalysis, with its interest in the subjective experience of the ‘patient’, that this tendency weakened.

Turkey: The cultural hegemony of the AKP has partly been achieved through the mobilization of women into Islamist NGOs. Ayşe Durakbaşa contrasts Islamist discourse on women with different currents of secular feminisms, particularly Kemalist feminism and second-wave feminism. She also explains how Kemalist feminists have been under attack not only from Islamists, but also, because of their affinity to Turkish nationalism, from Kurdish nationalists and Kurdish feminists.

More articles from L’Homme in Eurozine; L’Homme’s website

Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais (Portugal) 118 (2019)

In Portuguese social science journal Revista Crítica, historian Radina Vučetić looks back at the history of cinematic collaboration between Yugoslavia and post-colonial Africa. Beginning in the 1950s, Yugoslav film projects in Algeria, Mali, Tanzania, Guinea and Mozambique peaked in the 1960s. Vučetić focuses on the Yugoslav-Mozambican film Veceremos (1967), produced by the film company Filmske Novosti. ‘This documentary, devoid of any socialist ideology, greatly contributed to the internationalization of the anti-colonial struggle of African peoples.’

In the midst of the Cold War, Filmske Novosti avoided siding with either camp. Instead, its documentaries about the African struggle for independence focused on anti-colonialism, solidarity and the brotherhood of nations. ‘An unexpected result of this typical Yugoslav policy of non-alignment was that a new film genre of solidarity was created, which soon became a model for a great number of authors who were documenting other anti-colonial movements across the globe.’

West Germany: The African liberation movement received political and material support not only from the socialist states. In West Germany, writes historian Nils Schliehe, solidarity with Lusophone Africa in 1960s and early 1970s was partly a response to Bonn’s cooperation with the Salazar regime. After Portuguese independence in 1974, solidarity groups disappeared. As one campaign group put it: ‘The hope that we invested in the people of Indochina and the Portuguese colonies was unrealistic because we turned them into proxies for our own longing for liberation.’

Machismo: It is not quite time to bid ‘farewell to the Iberian macho’, writes Juan Antonio Rodríguez-del-Pino. Though research indicates a gradual weakening of the gender stereotypes cemented into Spanish society by the Franco regime, men are still afraid of ‘losing power in an uncontrolled space. And Spanish society in the process of becoming more equal is an uncontrolled space.’

More articles from Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais in Eurozine; Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais’s website

This is our 10/2019 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about latest publications and news on partner journals.

Published 5 June 2019

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.