The corona pandemic has brought globalization’s defects into sharp relief. Across the spectrum, neoliberalism is being challenged. Can the narrative of beneficent globalization be revived? And as US hegemony fades, can the institutions of global governance survive?

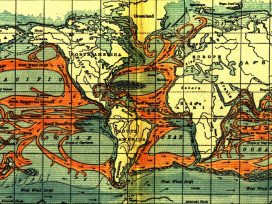

Around the year 1320, the Plague broke out in Hubei, the same central Chinese province, with its capital Wuhan, where COVID-19 originated. Despite all the historical differences, there are striking parallels between the course and consequences of both epidemics. It took 25 or 30 years for the Plague to reach the Chinese coast and take hold in the trade ports and the termini of the Central Asian caravan routes that connected China to Europe. From there it moved quickly, however: within a year the disease was raging in Tana on the Sea of Azov, the end of the Central Asian route, and in Aleppo, the end of the route through Persia. It spread just as quickly along the maritime route that ran through the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea, and then through the Red Sea to the Nile Delta or up the Persian Gulf and the Euphrates to the Syrian coast. There it was met by Italian galleys waiting to embark valuable goods from the caravans and distribute them throughout Europe. By 1348 the plague had hit Italy with full force.1

The political, social and economic consequences were catastrophic. In addition to the vast numbers of people who died along the trade routes and in trade centres, the plague also caused the collapse of the first global economic system, of which northern Italy and the Netherlands were the western periphery. The effects of the collapse were profound: a prolonged period of economic stagnation; the disintegration of the Mongol Empire; and the legacy of the Black Death, which left a deep mark on Europe’s collective memory and is kept alive today through plague columns and passion plays.

This globalization before globalization – the first world system, before Europe began its conquest of the globe – fell apart extremely quickly. The world remained fragmented for a long time, until the early Ming maritime expeditions restored the system from the East at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Seventy years later, the Portuguese discovered the sea route to India and established the ‘Estado da Índia’ as the new order in the Indian Ocean basin.2

QAnon reaches the Vienna Pestsäule, 1 May 2020. Photo by Simon Garnett

Grand narratives of globalization

Globalization is the intensification, acceleration and simultaneous spatial expansion of cross-border exchanges (trade, finance, migration, information and even epidemics). In other words, it is the compression of space and time. But as the coronavirus has shown, technical progress in transport and communication is not in itself enough. Globalization cannot take place without global governance: an institutional framework that guarantees the international public goods of economic stability and political security. This can be achieved by means of treaties and organizations, either by multiple actors in cooperation or through the efforts of a leading power, with others reaping the benefits as free-riders.3 The first guarantors of this institutional framework were the Mongols and the Italians. The role then passed to Ming China, then to Portugal and Spain, then to the Netherlands and Great Britain, and finally to the USA.

But there is something else that globalization needs: a grand narrative that can explain why it is normatively good and to the advantage of all involved. Without such a narrative, the respective powers could never muster the political will and resources needed to maintain globalization’s framework, establish its rules and, if need be, enforce them violently.

The original prophet of globalization was David Ricardo, who set out his famous theory of comparative advantage in 1817.4 Ricardo argued that international trade takes place – and should take place – because the international division of labour, by reducing costs, benefits all participants. This was a new paradigm that went against the prevailing theory of mercantilism. Ricardo did not just recommend an international network of free trade agreements, but also argued that it was legitimate to coerce other nations to open up to trade. He had several important precursors who also contributed to the grand narrative of globalization, including Hugo Grotius, the Dutch proponent of the principle of the freedom of the seas.5

The grand narrative of globalization in the tradition of Grotius and Ricardo would, however, have been ineffectual without advocates to expound and disseminate it, or powerful politicians able to assert the idea of liberalism. Globalization has depended on them for its momentum. From the middle of the nineteenth century, this role was assumed by Great Britain. It built up an interconnected system of bilateral trade agreements and, from 1842 on, used ‘gunboat diplomacy’ to force countries like China to participate. Japan yielded to American pressure and followed suit in 1854. So began the economic resurgence of China and Japan that had previously been hampered by self-isolation. Globalization was gathering pace.

Globalization in the twentieth century

Before the outbreak of the First World War, steamships and railways had taken globalization to new heights. Afterwards, however, Great Britain was too weak and the isolationist USA as yet unwilling to step forward as leader of the liberal order. This prevented a quick recovery from the Great Depression that began in 1929. A radical shift towards deglobalization was intensified by the Second World War. It was not until the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 that the USA took up the reins. The foundation of the World Bank, the IMF and the WTO – which repeatedly reduced tariffs, and whose jurisdictions were extended to services, capital movements and foreign investments – revived Ricardian thought and put globalization back on track.

With the collapse of the communist hemisphere and the rise of neoliberal hegemony in the 1990s, all who were not opposed to globalization as such, but only to the excesses of unrestrained market fundamentalism, pinned their hopes on global governance. Globalization would be kept under control through international organizations, agreements and norms. For a long time, this approach seemed successful, at least in Europe – despite the EU’s evolution into the motor of intra-European globalization.

Cosmopolitanism emerged as the domestic counterpart to globalization and global governance. The idea appeals to an upper-income, educated, mobile and multilingual class. These are people who support the free movement of capital and goods, as well as multiculturalism and universalist values. But a wider section of the population has also grown accustomed to the conveniences of globalization: cheap textiles and consumer electronics, exotic fruits all year round, holidays all over the world, unrestricted travel throughout the Schengen zone and migrant workers to do all the physically demanding or badly paid jobs.

Four convulsions

Doubts about the grand narrative first appeared in the West when the East Asian nations – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China – became more economically competitive. Globalization was turning out to be a zero-sum game. Industrialization in Asia came at the expense of deindustrialization in the West. The first American decline in the 1980s, precipitated by Japan – and the second American decline precipitated by China – weakened the grand narrative in the heartland of neoliberalism, with demands for protectionism now coming from the Rust Belt.

The second major crisis to hit the idea of globalization came in 2008, when the global financial crisis pushed many nations to the brink of bankruptcy. The convulsion was particularly violent because it affected not just global financial gamblers – euphemistically called investment bankers – but also ordinary people who had risked their savings in their desire for high returns. Zero interest rates on deposits and soaring property prices and rents, as the property market was flooded by capital on the hunt for new yields, were the price still being paid for the globalization of the financial markets.

Cracks appeared for the third time in the myth of beneficent globalization with the wave of mass migration to Europe in 2015. From a neoliberal perspective, migration – or at least the migration of workers – is a good thing. Given demographic change, it provides destination countries with urgently needed workers while also lowering the cost of labour. In countries of origin, it reduces unemployment and increases wages. In short, global labour markets are balanced. But, even more than competition from East Asia and the financial crisis, migration has had extra-economic consequences, the main one being the growth of populism, whose supporters are the antithesis of the cosmopolitan.

A fourth, heavy blow to the narrative of globalization came from the opposite direction. A succession of droughts, wildfires, torrential downpours, floods and storms had long been impossible to ignore, even for those not versed in climate policy. With Fridays for Future, ecology became a mass movement. For these critics of globalization, the answer lies in eating strictly local, organic food, using bicycles and public transport, and holidaying in one’s own country.

Despite his erratic tendencies, Donald Trump’s policies follow a certain logic. The USA is facing the classic hegemon’s dilemma of having to choose between status and power. To assert its status as guarantor of the liberal economic order – and so to ensure globalization’s future – would mean to risk its position as the foremost economic power. Were the USA to become a victim of globalization, it would no longer have the resources needed to assert its status in the first place. But to respond to the pressure of globalization with protectionist or even isolationist policies would mean forfeiting its status as world leader.

Trump’s ‘America First’ policy is a response to this dilemma. Reacting to the populists, he promises to bring jobs back to the USA’s former industrial belt. His task has become easier now that climate change has effectively made it impossible for cosmopolitan circles to defend globalization. Trump is on his way to becoming the most prominent proponent of a counter-discourse to globalization, and his actions align with his words.

China after corona

Meanwhile, China is unwilling to step into the USA’s shoes as the world’s policeman, though one might think it had a strong interest in doing so. But China does not follow the neoliberal narrative and has proven that industrialization and prosperity are possible by other routes. China is happy to take advantage of western liberalism in order to launch an aggressive investment campaign on the back of its export offensive. At the same time, however, it insists on bureaucratic control. As long as the new Chinese middle class benefits from the system, it will largely tolerate being denied the civil liberties associated with cosmopolitan globalization. China is waiting until 2049, the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic, to become the world’s leading power. Until then, its dominance extends only to the countries along the New Silk Road, which it entices with loans and infrastructure projects.

Hong Kong port. Photo by Modlem from Wikimedia Commons

Now, however, everything has changed. Since the outbreak of the coronavirus in Wuhan, China has become much less remote than it seemed. This time the virus spread around the world in 25 or 30 days, rather than years. It is not just China’s neighbours South Korea and Japan, or Iran, one of the links in the New Silk Road, that are affected. So too is Europe, with Italy again serving as the gateway. There is now widespread awareness that the pandemic is an expression of globalization. It has shown that the international division of labour leads not just to increased prosperity, but also to massive interdependencies. When face masks and protective clothing made in China can no longer be exported or have stopped being manufactured because of the pandemic, or when European pharmaceutical production is in danger because 300 precursor ingredients are also made in China, then globalization starts to inspire fear.

China and its leaders are now on the defensive. Economically, the country is faced with a severe downturn, whose duration and global impact are still impossible to predict. China’s size means that if it were to drop out as a supplier – both of finished goods or parts – or as a buyer, of oil for example, the effects would be enormous. Many companies will be weighing up whether it is sensible and necessary to outsource everything to China for the sake of marginally reduced costs. Many will have started long-term preparations for bringing at least some of their manufacturing back in-house. This is certain to be the case for the pharmaceutical industry, especially as political requirements legitimized by national emergency are likely to be introduced in the sector. The coronavirus has succeeded where Trump and his tariffs have failed.

China’s leadership also faces pressure from the population. Censorship and a government-controlled press have led to widespread mistrust of the CP’s information policy. The public blames local party leaders for keeping the outbreak of the virus under wraps for too long and for disregarding early warnings from doctors. In foreign affairs, where China was already on the back foot after the protests in Hong Kong and the reports about the Uighur camps in Xinjiang, it will probably be a long time before China regains the offensive. For the time being, China is unlikely to assume from the USA the role as prime mover of globalization. Even the New Silk Road seems to have been temporarily abandoned.

Neoliberalism without supporters

The grand narrative of globalization is currently being questioned as much by its purported winners as by its losers. Cosmopolitan criticism focuses on globalization’s impact on the environment, while populist criticism focuses on deindustrialization, migration and cultural change. Coronavirus has made this abundantly clear through its transformation of everyday life. It has sparked concerns about a global economic crisis with mass unemployment and has revived old fears about the ‘Yellow Peril’ that supposedly threatens the West.

Supporters of the neoliberal paradigm are under attack from both sides. As globalization becomes increasingly unpopular, politicians will be less and less willing to maintain the resources, regulations and institutions that underpin it. Trump and those who share his ideas will find their task easier: without global governance, globalization has no power.

The first week of March 2020 may therefore go down in history not just as the beginning of a deep economic recession, but also as the moment when the wheel of globalization was once again halted. The losses will not be as serious as in 1350, when the plague held Europe in its grip, but neither will they be a mere blip for the world economy. The international division of labour cannot be completely undone, but its excesses can.

It will not take as long as it did in the fourteenth century for the global economy to recover. But the liberal world order needs a new guarantor. The incumbent has grown tired of the role, Europe is too weak and too disunited, and China’s idea of the world order is not liberal but bureaucratic. For the foreseeable future, the workings of globalization will continue to creak under the strain.

For routes and dates see Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350, New York, Oxford University Press, 1989, 8.

According to world systems theorists following Immanuel Wallerstein and André Gunder Frank.

See Ulrich Menzel, Die Ordnung der Welt, Berlin 2015.

David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, London 1817.

Hugo Grotius, The Freedom of the Seas, trans. R. van Deman Magoffin, New York, Oxford University Press, 1916 [1608].

Published 4 May 2020

Original in German

Translated by

Isabelle Chaize

First published by Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik 4/2020 (German version); Eurozine (shortened English version)

Contributed by Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik © Ulrich Menzel /Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Zones of friction

An interview with Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

Extractivism and its impacts seem to be globalization’s end game. Industrial capitalism plunders natural resources, wreaking havoc on biomes and the lives of Indigenous peoples – then moves on. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing speaks about the ‘friction’ between dynamic groups that can ultimately bring regeneration.

World makers of the Black Atlantic

Adom Getachew talks to Ashish Ghadiali

The history of decolonization tends to be understood as the incorporation of formerly colonial states as sovereign equals to international society. But this liberal narrative overlooks the revolutionary roots of the anti-colonial project in opposition to the exploitative and hierarchical system of empire.