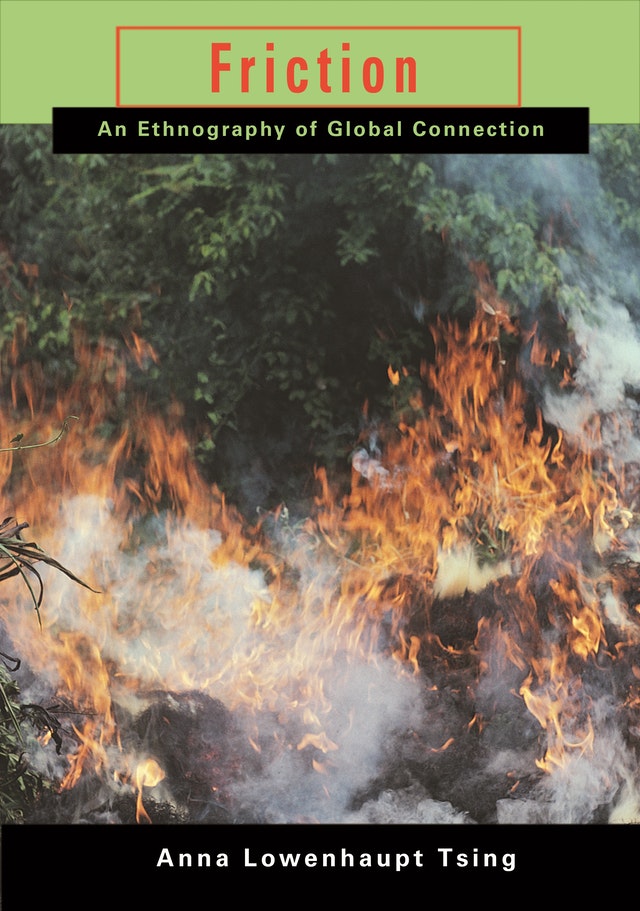

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton University Press, 2005), as mentioned in her interview with Culture & Démocratie.

Friction tells the story of a ‘frontier zone’ in late 20th century Indonesia. We witness the end of a tropical forest in the Meratus Mountains of South Kalimantan. Forest clearing, single-crop agriculture, fires and erosion have made this land uninhabitable for its Dayak population, due to international demand for timber, rubber, gold and palm oil. Friction describes how ‘imperial’ extractivism degrades our attachments and makes our homes uninhabitable.

Interaction between heterogeneous zones caused friction in South Kalimantan: with the fall of General Suharto, the Meratus forest became a zone of friction where corrupt provincial authorities met with forest engineers, the army, gangsters, indigenous populations, Muslim activists from the capital, nature lovers, slash-and-burn cultivation, scientific institutions, international companies, illegal loggers and bees.

Faced with this list, where ‘global interconnections’ come up against cultural particularism, we cannot but think of another more familiar, current friction, involving a pangolin, transnational air routes, activist doctors, Chinese officials, illegal markets, a BSL-4 high tech lab, conspiracy theories, fake news, deforestation, a virus, the global economic crisis and individual confinement.

A burnt out tree stands where an entire forest used to in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by Josh Estey/AusAID, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: It seems the effects of globalization are being felt more and more often in our day-to-day lives, ‘at home’, when we once believed them to be manifest only in faraway, wild forests. Are we going to be forced to leave our homes, as many have in Australia and on the US West Coast, surrounded by fires?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: Global connections have been part of human life for a very long time. If you think about where the ingredients in even an ordinary meal come from, the breadth of connections is evident. Through most of human history, however, privileged people have been able to use those connections for their benefit, rather than having to run away from their destructive power.

Recent environmental disasters have distinguished themselves in displacing and threatening the lives even of elites. The bright side of this is that it becomes hard to deny that something is wrong. Suddenly it is clear that the cruel and flimsy barriers that were supposed to limit damage to humans and other beings imagined as unimportant will not hold. There is no place to run and no place to hide.

In her essay The ceremony found, philosopher Sylvia Wynter glimpses the possibilities of a new, more inclusive ‘humanity’ in the ruins of elite protections. Bruno Latour imagines it might lead to an alternative to Left versus Right political dichotomies, to instead show us the dangers of ‘Out of this World’ claims and the importance of a reorientation toward living within what’s possible on Earth. These are useful gestures toward possibility. At the same time, living through disasters is terrifying – and it’s never clear whether and for how long we will live.

This article is from Culture & Démocratie. Read our review of their Special Issue 2020.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: The ‘frontier zone’ of Kalimantan is a zone of friction in the sense that it arises out of interaction between ‘legitimate and illegitimate partners: military and gangsters, gangsters and corporations, builders and plunderers’, and from the ways in which its actors undo traditional ties and attachments between the forest and its inhabitants in order to reduce part of it to ‘resources handed out as commodities to corporations by bureaucrats and generals’.

Is a frontier zone always a translation zone, where the material and the imaginary are intertwined to produce muddled histories? How do economic requirements transform the Dayaks’ ways of being, of living, their attachments to their homes in wild nature so as to make its systemic exploitation possible?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: We live immersed in translations; I can’t think of any place that is not a translation zone. Indeed, the material and imaginary are intertwined in muddled histories. The special quality of the frontier is that it normalizes violence as a method of displacement and dispossession. Frontier violence attempts to sweep away Indigenous communities and ecologies in a chaotic maelstrom. And yet frontier violence can be seductive, drawing local people into the dangerous pleasures of boom-and-bust resource economies. For example, in Friction, I describe a gold boom in which people hosed down whole hillsides with high-pressure hydraulic pumps just in case a few grammes of gold might be somewhere in the gravel below them.

In much of Kalimantan, frontier violence made way for the terrifying order of vast oil palm plantations, stretching as far as an airborne observer can see, and in every direction. In those places, there is not even a hedgerow left; there are no refuges for plants and animals, less the people who depend on them. Most ironic, indeed, are corporate attempts to claim carbon credits for oil palm plantations as if these were forests. Oil palm plantations are sites of extinction; they are landmarks for the brutal inattention to planetary survival that continues to characterize our times. Even in the 1990s, when the oil palm was first coming in, I saw forest animals flocking into villages, where they knew they would be killed. With the total destruction of the forest, there was no place left for them to hide.

My Kalimantan brother, the man I call Ma Salam in Friction, invited me to return to his village this past summer, although, unfortunately, our plans were interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. He showed me photographs of his village and spoke of their communal struggle to save the forest in that area. It is heartening to know that at least some pockets of village and forest remain.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: In his article A Place for Stories: Nature, History and Narrative, William Cronon explains how the concept of wilderness has been the theatre of competing narratives. For Walter Prescott Webb, for example, US Great Plains are a resistant landscape that technological innovations will finally succeed in taming and transforming. For Frederick Jackson Turner, it is the pioneers’ individual strength and freedom that transformed wilderness into farms and gardens.

But all these narratives of the wilderness have the elimination of the fact that the Great Plains were already inhabited before the settlers arrived in common. Wilderness is a way to erase US violent colonial history by replacing the slaughter of Native Americans with the story of heroic pioneers struggling against a hostile and uninhabitable nature. Cronon writes: ‘We inhabit an endlessly storied world’.

It seems you are saying something similar when you write that the stories of globalized capitalism are neither pure nor universal but rather heterogeneous patchworks. You mention, for example, John Muir who needed support from the railway industry to create Yosemite National Park, which developed tourism against the will of local communities. In turn, locals defended their hunting rights, a viewpoint that contradicted Muir’s romantic and religious vision of a wild, uninhabited nature. Is nature always a mixture of history and lived reality, of magic and reality, a social-ecological system?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: For many urban dwellers – including me, until the time of my fieldwork – forests appear to be timeless, outside of history. This could not be farther from the truth. The campus where I teach, the University of California, Santa Cruz, is full of beautiful redwood trees. At first the forest seems a timeless, magical paradise. But a closer look shows that the trees surround giant stumps: the whole redwood forest was cut down in the early 20th century and today’s trees are shoots from those old rootstocks. Forests are always historical – and the habits through which we learn to forget this blind us to the dynamism of nature. The best nature magic is in the history – in not forgetting it.

The Kalimantan forest had a lot to teach me about this. The Dayak community, with whom I lived, practices an agroforestry system in which small fields are made every year and slowly allowed to return to forest again. This means that the landscape closest to settlements is a patchwork of regrowing forest. Any local person can look at a hillside and see the different time frames of farming: the light green of young brush, enhanced with saved and planted trees; the deeper green of secondary forest; the darkest green and great emergent trees of the oldest forest. A Kalimantan hillside is a human history as well as a more-than-human one. The regrowth of forest patches is the story of movement, of community fusions and fissions, of births and marriages and new children and deaths. In mapping household movements and old farms, I learned to see the human as well as non-human histories of the forest. By the time I came back to California, I could never see the forest as timeless again.

That forests change historically, and together with humans, does not make them impervious to human damage, however. So many commentators seem to think that, once natural histories are recognized as mixed up with human histories, there must be no difference between a forest and a parking lot, since both are anthropogenic. This is nonsense. Recognizing the historicity of nature, and human roles within it, makes it important to be more careful than ever in respecting non-human timelines and conditions for living.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: In The Mushroom at the End of the World, you tell the story of yet another forest, a forest on the US West Coast destroyed by systematic cutting down of the great trees, which brought about the ruin of the local forestry trade. In this story you explain how the matsutake mushroom, which grows on poor soils in symbiosis with pines, appeared. This mushroom is highly prized in Japan, where it is an important part of Japanese culture. The matsutake took the interest of Vietnamese boat people, who had settled in those forests and were in touch with Japanese traders. Then forest engineers, former loggers and international trade entered that strange story.

You show how pines, by making the growth of the matsutake possible, have allowed both uprooted and cosmopolitan populations – loggers as well as Vietnamese migrants – to invent a way of inhabiting the ruins of capitalism. Isn’t escaping TINA (there is no alternative) also an ability to explore these interstitial zones, which you call ‘gaps’?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: We are really lucky, as human beings, that industrial capitalism does not live up to the promises it makes – to fully rationalize the earth’s resources and expend them for its use. We are only alive because this promise has not been fully fulfilled, at least, so far. Logged industrial forests sometimes come back in other forms, such as the lodgepole pine groves of central Oregon, where aromatic and valuable matsutake mushrooms grow. The industrial oil palm plantations of Kalimantan are a difficult case, however, because the conversion of forest into a monocultural commodity has been so thorough and so vast that many potential alternative futures for livability have been squashed. As Sophie Chao has shown for West Papua, oil plantations are a dead zone, a place where maps of multispecies livability stop – and, indeed, from whose borders violence and death spread.

One could say that one of the central challenges of our times is to figure out which kinds of human ecological disturbances allow livable futures and which do not. Friction describes a moment in the forest of Kalimantan when such futures were in the balance. Indigenous groups were fighting for the forests, both as a source of livelihood and as a space for more-than-human life. Such struggles continue but now within the tragedy of the spreading dead zones of oil palm plantations. Both Indigenous people’s agroforestry and oil palm plantations are forms of human disturbance. But as I mentioned above, not all kinds of disturbance can be equally embraced. It’s key to earthly survival to stop some kinds even while appreciating human entanglement in all of earth’s ecologies.

When I published The Mushroom at the End of the World, which tells a relatively benign story of the remaking of logged-over forests as zones for commercial mushroom picking by refugees and other disadvantaged people, some readers took this to mean that we could stop worrying. They thought everything would work out in the end despite capitalist ecological destruction. I had not meant to convey a message of transcendent hope, hope that overcomes all.

In fact, I think the Earth is in rather dire straits these days and unthinking optimism is not going to help anything. Mushroom tells of more-than-human precarity and the need to negotiate ruins. Collaborative survival is the best we can do, but it’s hardly the light at the end of the tunnel. Instead, to foreshadow one of your later questions, it’s doing our best to live in the middle of things. This is not the same as the kind of hope that refuses bad news.

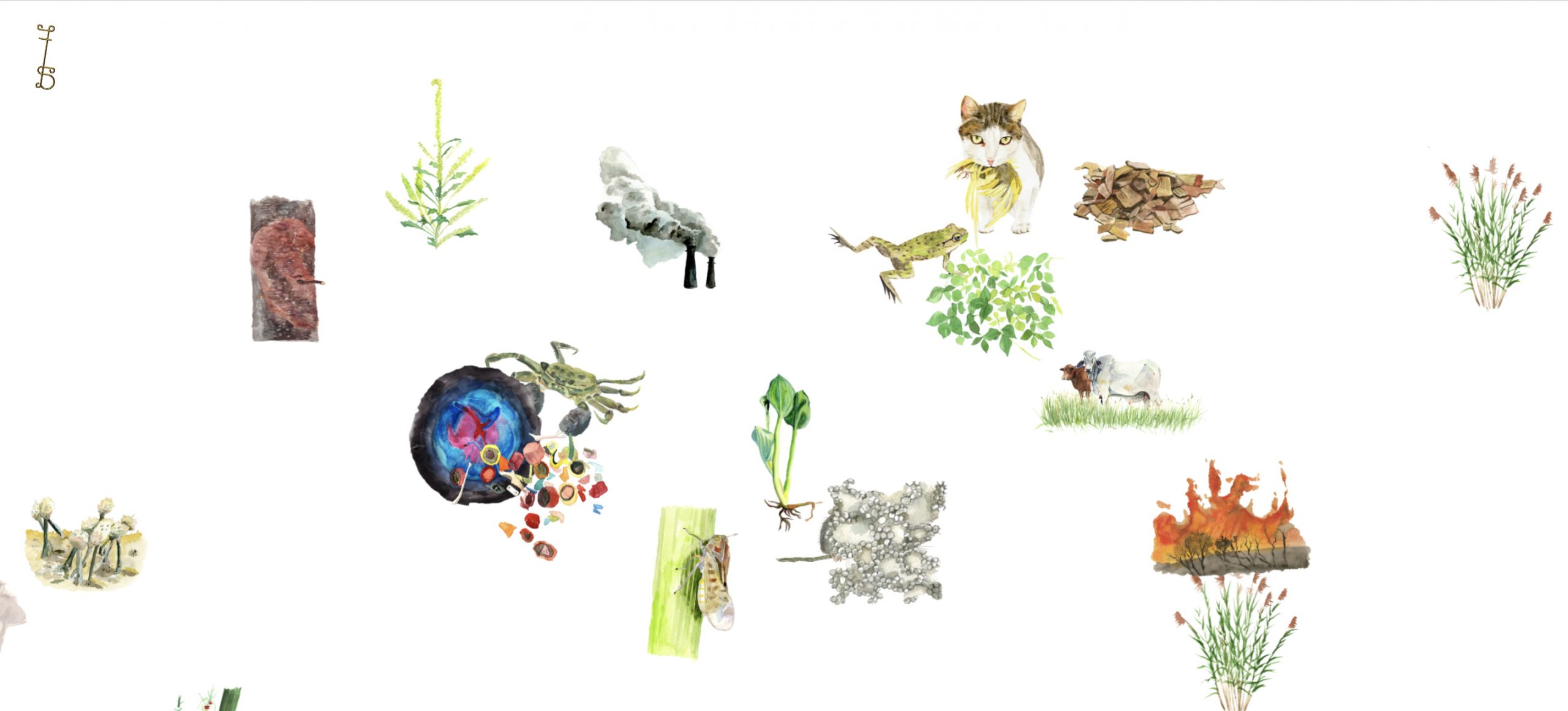

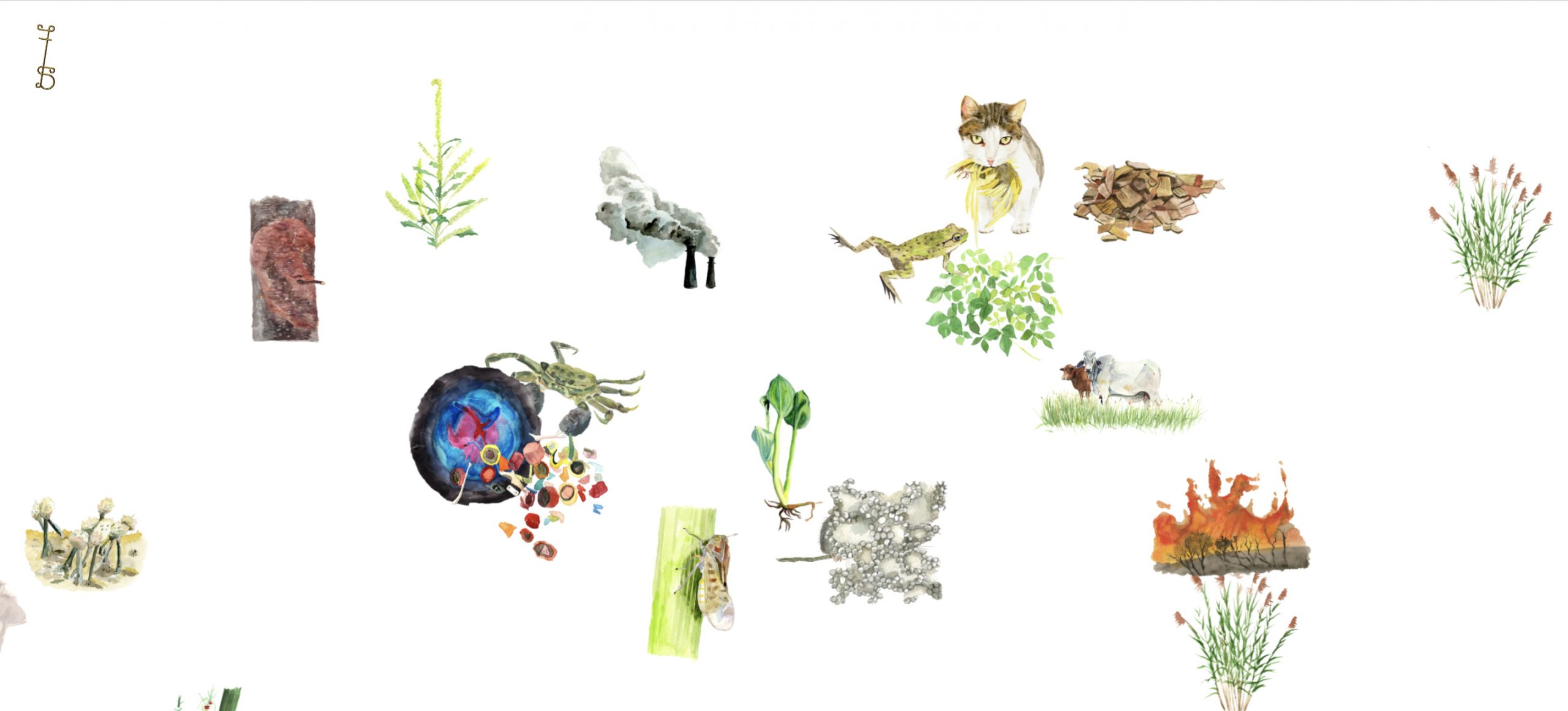

I began to worry that we have collectively lost track of ways to tell bad news. I’m so glad that Friction is now out in French. It is an attempt to describe more-than-human destruction without giving up entirely. Friction offers a set of tools for assessing our situation in the middle of things. My new project continues this trajectory of thinking in a digital form. It is a collaborative art-and-science project: Feral Atlas: The More-than-Human Anthropocene. This project works on arts of storytelling in which transcendent hope is disavowed in favor of what Donna Haraway calls ‘staying with the trouble’. Friction, too, is a project for learning how to stay with the trouble by attending to the conjunctures we all find ourselves in – and the multiple alternative futures to which they might lead.

FERAL ATLAS by Anna L. Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena and Feifei Zhou. Published by Stanford University Press (c) 2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. All rights reserved. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: Your books are a way to fight the fatalism of globalized capitalism. We need to tell other stories and to accept that our stories are muddled ways of inhabiting the world. In Staying with the Trouble, Donna Haraway writes about SF, standing for science fiction as well as string figure, scientific fact or speculative feminism – a way of tying together, to be responsible, to produce common unexpected or risky patterns, to accept ambivalence and misunderstanding. In Friction and The Mushroom at the End of the World you weave your own SF/string figures in order to resist injustice and a world deprived of attachments, where speed and lack of responsibility prevail. Is it possible to do SF politics and ethnography?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: My writing is both a set of stories and a reflection on storytelling, and Haraway’s admonishment to stay with the trouble is very much on my mind. So, yes, ethnography is a kind of SF. Ethnographers organize the empirical materials of their research into a story and sometimes even a parable.

Friction offers an array of different kinds of storytelling practices, each of which intends to inspire students and scholars to consider events in the worlds they know best through these ways of knowing. Each chapter offers a tool – such as articulation or gaps – through which we might enter into world making projects, whether our own or those of others.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: In the last part of Friction, you tell the story of the weaving of an unexpected pattern between Dayak village elders, mountaineering and nature lovers, and Muslim activists from Jakarta. Their string figures have succeeded in overcoming the plans of a logging company to illegally clear a portion of the Meratus forest inhabited by the Dayaks. But when the various actors of this anti-logging campaign told you what happened, it turned out they all told a different story. In which ways can misunderstandings and muddled stories open new possibilities and produce hope?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: This section is intended as the climax of the book, the place where the reader can see how friction works. And, despite so many different ways of ‘doing forests’, the protagonists in this anti-logging struggle manage to work together. This is an example of the coalition building that is so important to any political mobilization we can hope for in a world in which we can’t afford to confuse other people’s situations with our own.

Hélène Hiessler and Sébastien Marandon: How can we inhabit disaster? How can we feel at home in a world where the extractivist logics of economic growth detach us from our environment, from our ‘middle’ – as in Isabelle Stengers’ invitation to ‘penser par le milieu’ (‘think from the middle’)?

Against universals, extremes, shouldn’t we favor situated ways of thinking, ways of thinking that care for their surroundings, for the place they inhabit, ways of thinking that pay attention to their attachments to others?

Isn’t it also what ‘friction’ is – accepting that my way of thinking comes up against, negotiates with, translates and counter-translates the others’ reasons and interests in order to invent different ways of inhabiting our places, together with other living beings?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: Perhaps we need to learn to live without ever feeling at home. Domestication, including of ourselves, may be part of the problem. We have learned to imagine forms of safety and companionship that limit themselves through property and patriarchy, forms that depend on violence for control. This is not the only way to imagine our lives. ‘Thinking from the middle’ seems just right to me – but the middle is often an uncomfortable place, without safety and buffeted by winds from so many different directions. This is not a call to be miserable. There are many joys along with dangers in that middle space.

As I worked on these questions, I went for a short walk to think and I guided my steps to a grassy place where I had seen meadow mushrooms still too tiny to pick two days before. I had marked the buttons with red fallen leaves to remember the spot. But someone had stepped on them – smashing them. Still, I gathered the remains to take home for a saute. Living in the middle of things is something like that: cooking with smashed mushrooms.

Friction is an acknowledgement that there is a lot going on. Just because one set of enthusiasts think their way of doing things, smashing all other trajectories, will win out, does not mean they are right. Perhaps ‘modernity’ is too wrapped up in the assumption that plans will be fulfilled according to the specification of the engineers who made them. The world does not work out that way. As each of the world-making trajectories with which we live rubs up against others, the friction recreates our situations. It’s what we have to work with.

This interview, conducted in English, was translated by Culture & Démocratie and originally published in French.